The narrative of Kinshasa’s popular culture and its ferments also adapt to developments in communication media by jumping on technological innovations boosted by new information and communication technologies.

This narrative has always been found on a large scale in popular music, the Congolese rumba popularised by the stars, as well as in television dramas commonly referred to as “Maboke” which are regularly broadcast on local television channels; and especially through popular comics, including those of the famous Papa Mfumu’eto.

Today, there are also hybrid television programmes and shows that are difficult to characterize and unclassifiable, such as “Lingala facile”[1], “Kin makambo”[2], etc., which combine everyday events with the focus on the “scandal”. The internet is also full of videos hosting musicians as well as famous Congolese personalities in order to get viewers to click on the catchphrase “polemicise or launch attacks” and increase the number of views on their Youtube channels.

As mentioned earlier, information and communication technologies (ICT) have shifted this narrative to the digital and social networks are spreading this content to their heart’s desire. The number of consumers is gigantic because they are obsessed with the content disseminated there. Especially those of the Congolese diaspora remain, in majority, connected to their country by this means and feed their imagination via this content. Laughing.

The keywords in this narrative remain the “sensation” and the “scandal”, which somewhat paradoxically coexist with the “moralistic” approach in the background.

The scandal is a serious issue that can involve or compromise important figures that shakes and outrages public opinion. It is an outrageous fact or event that provokes indignation.[3]

The codes of Mfumu’eto and the Youtubers

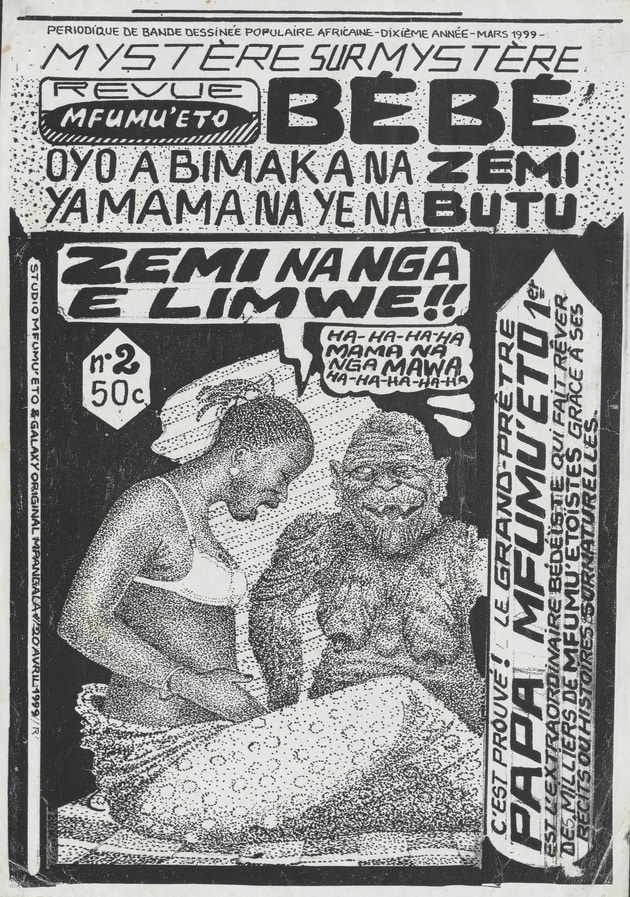

Courtesy of the Papa Mfumu’Eto 1er Papers, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida.

https://ufdc.ufl.edu/collections/mfumss/

Looking at the multitude of episodes of Papa Mfumu’eto, it is easily noticeable that the scandal occupies the central position in his stories. Even the titles suggest this at first glance: Nguma ameli muasi (A boa swallowed a woman), Pastor akangi ngando ya mystic a lata rosary (A pastor neutralises a devilish crocodile wearing a rosary), Baby oyo abimaka na zemi ya maman naye na butu (The story of a baby who comes out of his mother’s womb every night), Magic ya somo na kati ya National Anthem ya Zaire? (Is the national anthem of Zaire pure magic? ), etc.[4]

Photo of Revue Mfumu’Eto: »Bébé Oyo Abimaka Na Zemi Ya Mama Na Ye Na Butu«, 20 April 1999, Cover Image, Courtesy of the Papa Mfumu’Eto 1er Papers, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida.https://ufdc.ufl.edu/collections/mfumss

Likewise, images of celebrities are used to attract viewers through headlines such as: Ya mungul akei koluka mosala na AFDL? (Did Munguludiaka look for work at AFDL?), Mobutu akomi fazeur? (Has Mobutu become homeless?), etc.[5]

This selection of comic book issues was massively consumed at that time because of the accessibility in local distribution, the price, the simplicity of both verbal and iconic language, and the self-identification in the stories told.

The current YouTube chronicles are of course not about fictional incidents like those of Mfumu’eto, rather they are about true incidents, but the two make use of almost the same linguistic elements. Access to the internet makes it easier for many to be connected, the language used is mainly Lingala, the visual social codes are the same, the people respond to the same profiles and the titling techniques are the same, for example: Urgent sextape ya Moise Mbiye scandale sextape (Urgent! Sextape de Moise Mbiye Sextape scandal); Kake! Après FR Michel, Moise Mbiye scandale sextape (Breaking News! After FR Michel, Moise Mbiye sex tape scandal); Ken Mpiana atindeli Koffi Olomide message ya somo (Ken Mpiana sent Koffi Olomide a scandalous message), Etumba ! Sankara Dekunta asasi nde ko sasa Zacharie (Scandal! Sankara Dekunta massacred Zacharie). A selection of titles and links that are accessed and followed en masse; this can be witnessed by the number of views or people who clicked on the links.

[1] To see on Youtube.

[2] See also at Youtube.

[3] Microsoft® Encarta® 2009 © 1993-2008 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

[4] Nancy Rose Hunt, »Papa Mfumu’Eto 1er, star de la bande dessinée kinoise«,

Beauty Congo, 1926-2015: Congo Kitoko. Exhibition catalogue, 2015, pp. 276-281.

[5] Dito.