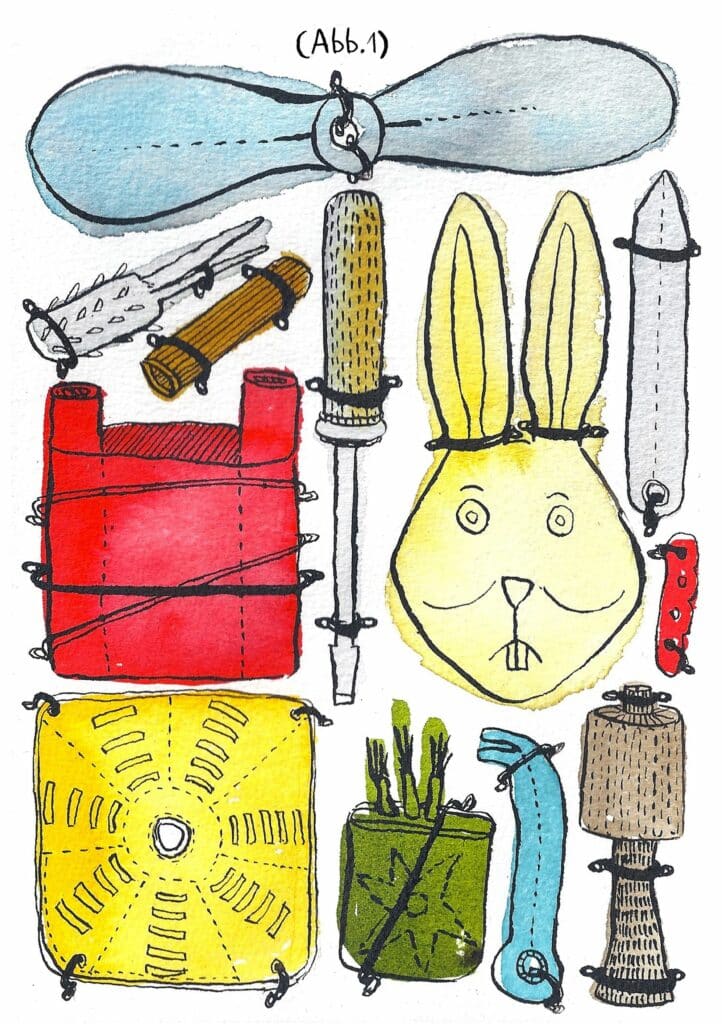

Ask me anything about Congo, because I was there for four days, I know my way around. In general, I am an expert (fig.1) on Africa, because I grew up in Uganda and Kenya and own a traditional African wax-print dress. From a European point of view, that seems to suffice for the whole continent.

As if it were that simple (fig.2).

Fig. 1 © Birgit Weyhe

Fig. 2 © Birgit Weyhe

Let’s take my wax-print dress. My daughter was friends with a Ghanaian girl in primary school. When her mother heard that my brother, who lives in Mozambique, was getting married and that I would be travelling for the wedding, she had a dress made for me out of wax-print fabric, because it would definitely dress me adequately (fig.3), as wax-print is worn all over Africa. She is right – the capulanas of Mozambican women are also made of this fabric and are therefore omnipresent.

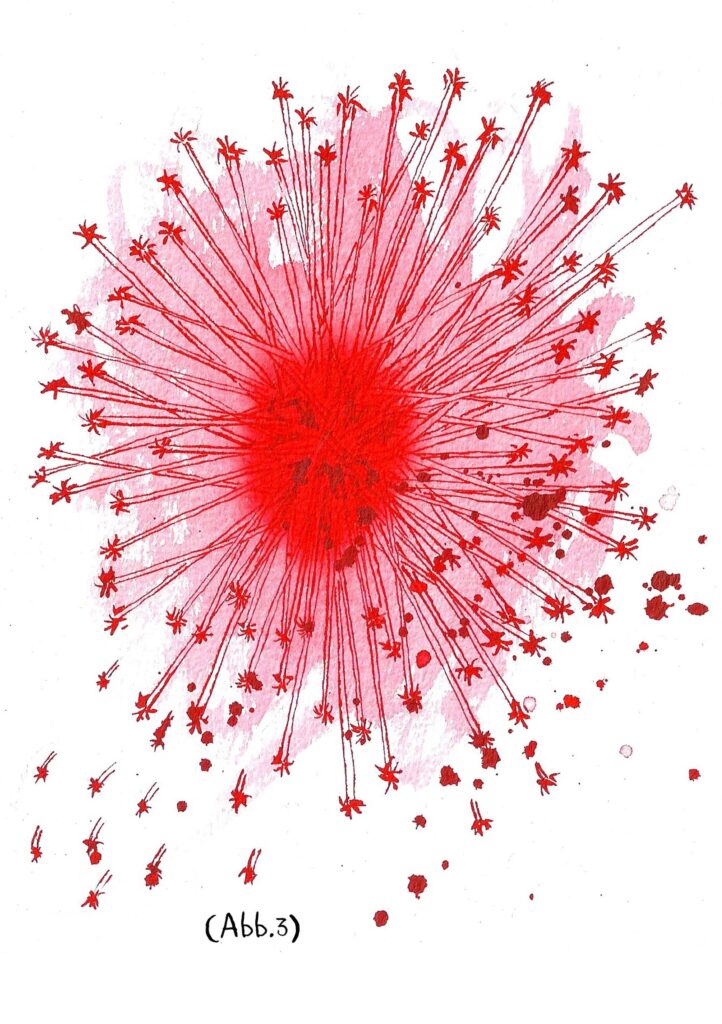

The interesting thing is that wax-print is by no means “traditionally African”. Although these fabrics are indeed worn in large parts of the continent, including the Congo, their history is a colonial one (fig.4).

Fig. 3 © Birgit Weyhe

Fig. 4 © Birgit Weyhe

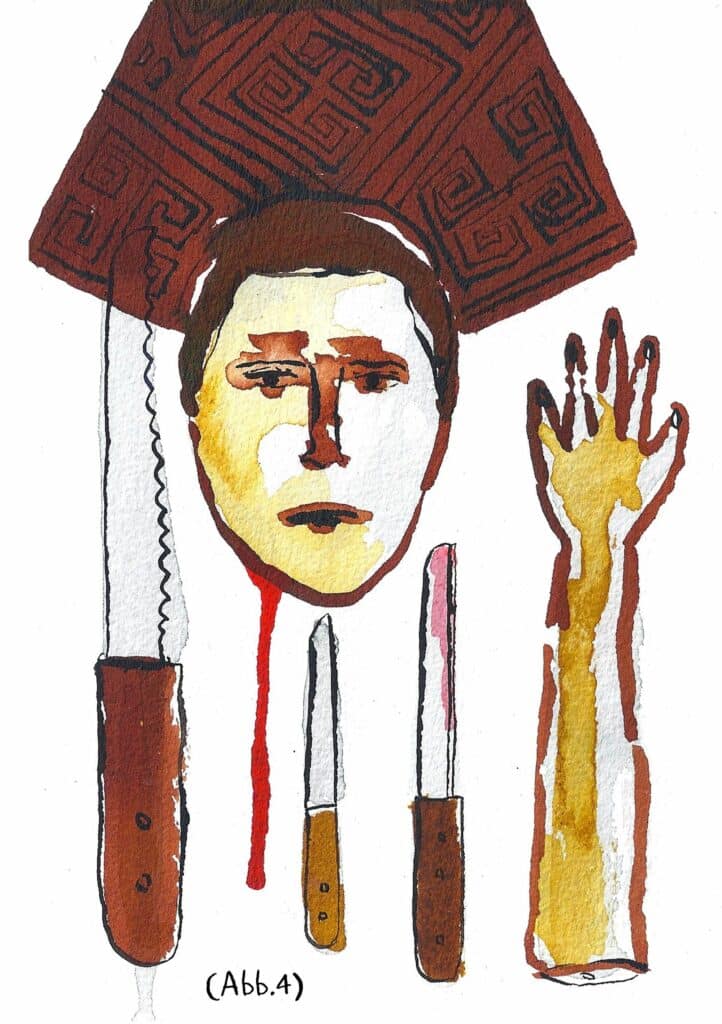

Wax-print fabrics, also known as Dutch Wax or Wax Hollandais, are printed cotton fabrics with colorful patterns on both sides. Originally, the wax print process was developed in the Netherlands in an effort to copy the patterns of Indonesian batik fabrics and produce them industrially as textile prints. The Javanese term batik refers to a reserve dyeing technique, where the dyeing is done with a color repelling liquid or paste such as wax, resin or starch. The reserve material is applied, drawn or stamped onto the fabric so that these parts of the fabric are protected in the dye bath and a bright pattern appears when the reserve material is removed. Hence the name Wax-Print or Dutch Wax. The Dutch wanted to market these industrially produced fabrics in their colony of Java at the time. The attempt failed because the Indonesians preferred their own traditional handicraft to the mass product (fig.5).

So at the end of the 19th century, the Dutch East India Company looked for an alternative market for its product and offered it for sale on its trade routes. On the West African Gold Coast, today’s Ghana, there was a great demand for the colorful patterned fabrics. Through contacts of Dutch traders with mission stations and targeted market research, detailed information (fig.6) was gathered about the clothing behavior of the Gold Coast inhabitants and their preferences for certain fabric patterns.

Fig. 5 © Birgit Weyhe

Fig. 6 © Birgit Weyhe

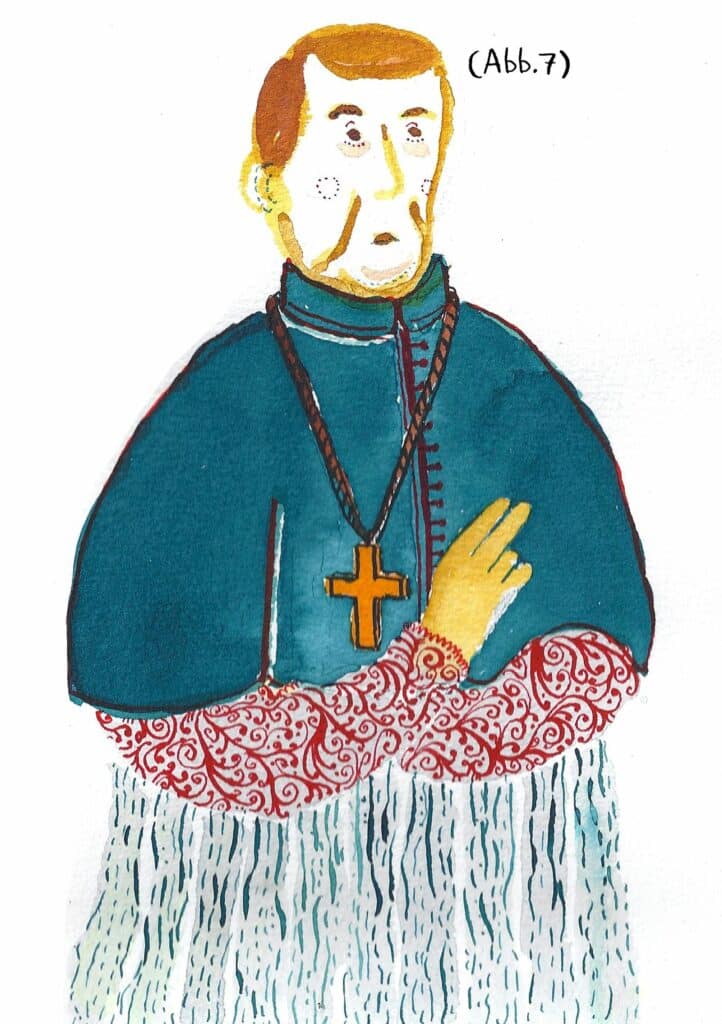

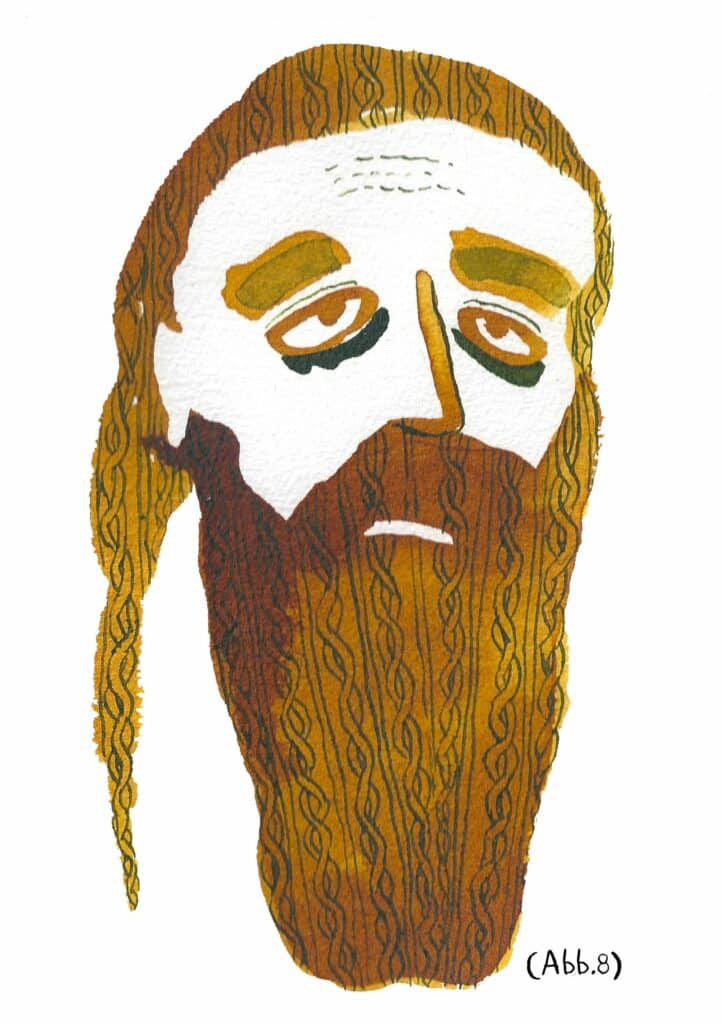

To increase profits, these findings were taken into account in production. In addition, the missionaries (fig.7) had an interest in enforcing a European dress code, as the nakedness of the population was not compatible with the laws of Christian morality to be implemented (fig.8).

Fig. 7 © Birgit Weyhe

Fig. 8 © Birgit Weyhe

Today, the Netherlands still dominates the market for wax-print fabrics, although it has now received competition from English, Chinese and Ghanaian companies.

Or let’s take my own biography. I grew up in the 70s and 80s first in Kampala, Uganda, then in Nairobi, Kenya. When I returned to my native city of Munich at the age of 19, I felt very foreign (fig.9).

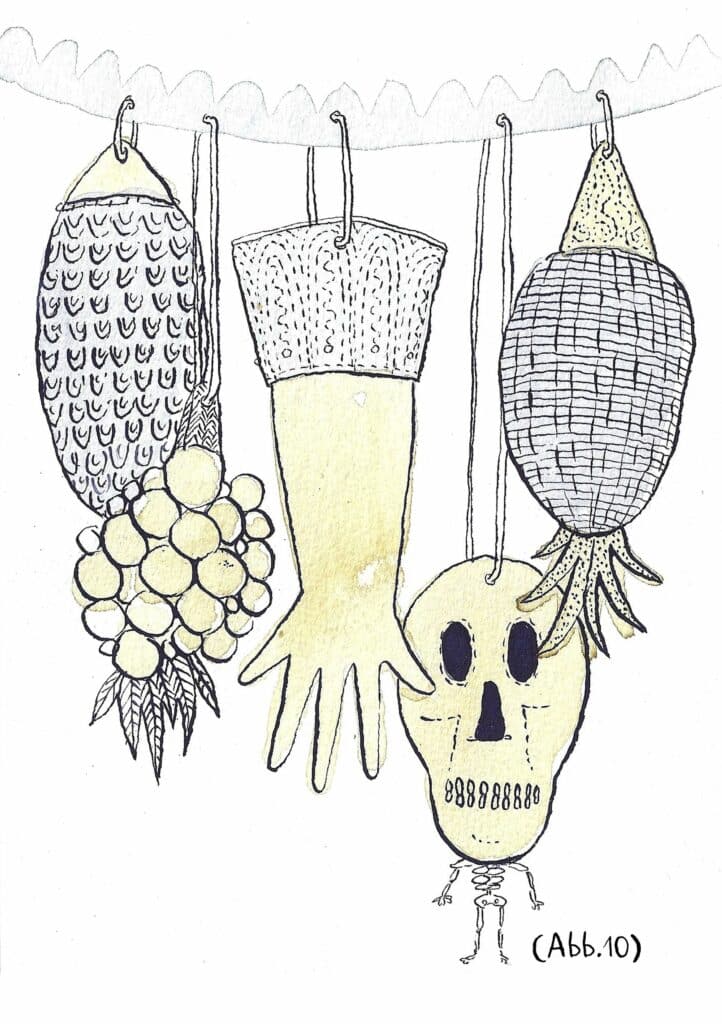

Above all, I was surprised by the undifferentiated view of Africa. No one knew more about it and no one was interested in anything beyond the usual exotic clichés (fig.10). It was always just “Africa”, never a specific country, a specific language, or a specific regional characteristic.

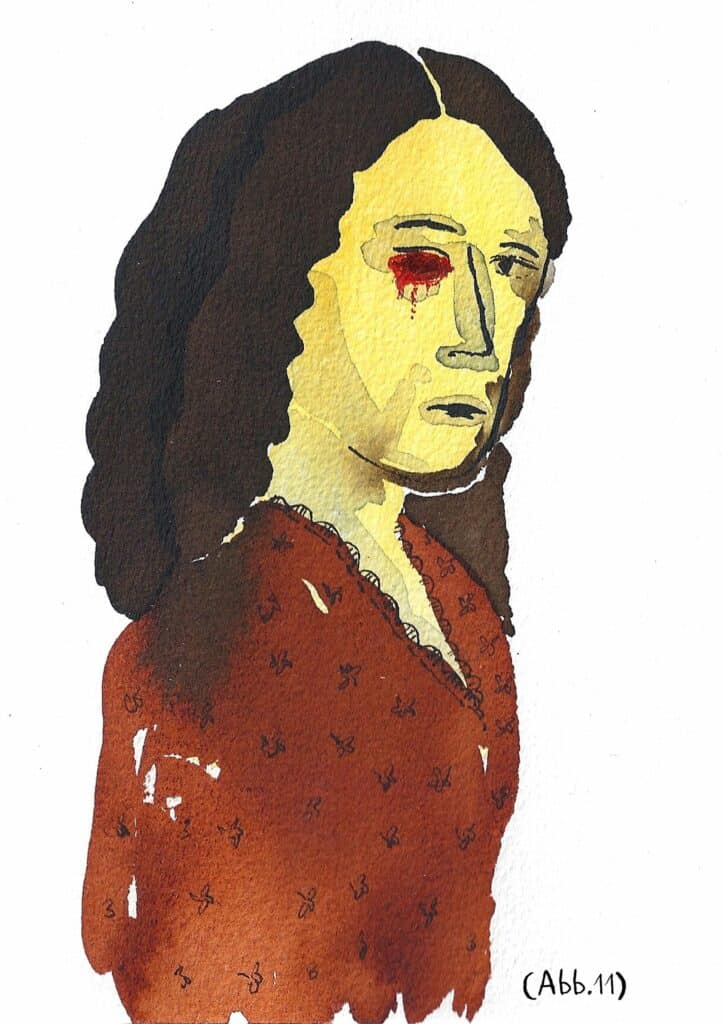

The African continent was divided up in 1884/85 at the so-called “Berlin Conference” among the representatives of 13 European states, as well as the USA and the Ottoman Empire; Africans were not present at this meeting. Many of the arbitrary country borders placed on the drawing board at that time still exist today. So there is a historical obligation for us Europeans to take a closer look (fig.11).

Fig. 10 © Birgit Weyhe

Fig. 11 © Birgit Weyhe

When I started drawing comics, I wanted to try to tell more differentiated stories about this continent. This means that I can only tell stories about certain places that I know. I hardly speak any French and have never been to West Africa except Nigeria. I don’t know North Africa either. I could only illustrate German Calendar, No December, not narrate it. And the corrections of my drawings were done by the Nigerian author of the story, Sylvia Ofili, and the publisher, Bibi Bakare-Yusuf. In the comics where I dealt with Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Mozambique or Nigeria, I also had to deal with my own privileges, my skin color, my origin. My stumbling (fig.12) and searching (fig.13) can be traced in my works.

Fig. 12 © Birgit Weyhe

Fig. 13 © Birgit Weyhe

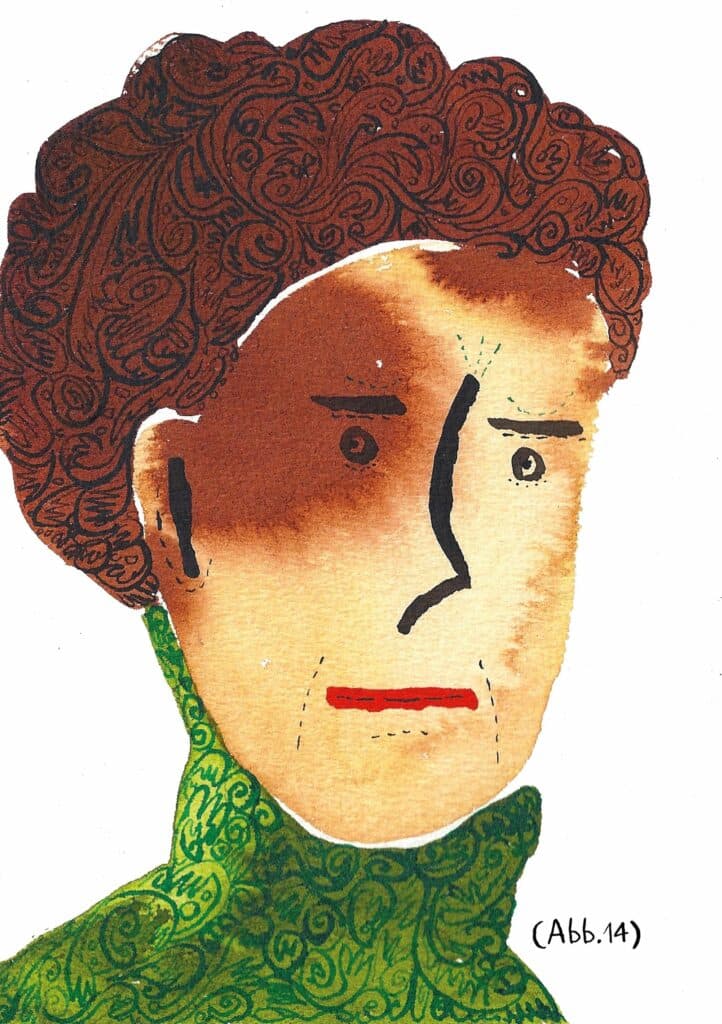

For example, in the representation of skin color. My first comics were drawn in ink, pure black on a white background, and all the black protagonists looked like blackface. In the next attempts, I thinned the ink so that it would be more glazed and more like a skin tone rather than overpainting. The result was similarly unsatisfactory, as all the subjects looked blotchy and skin diseased (fig.14).

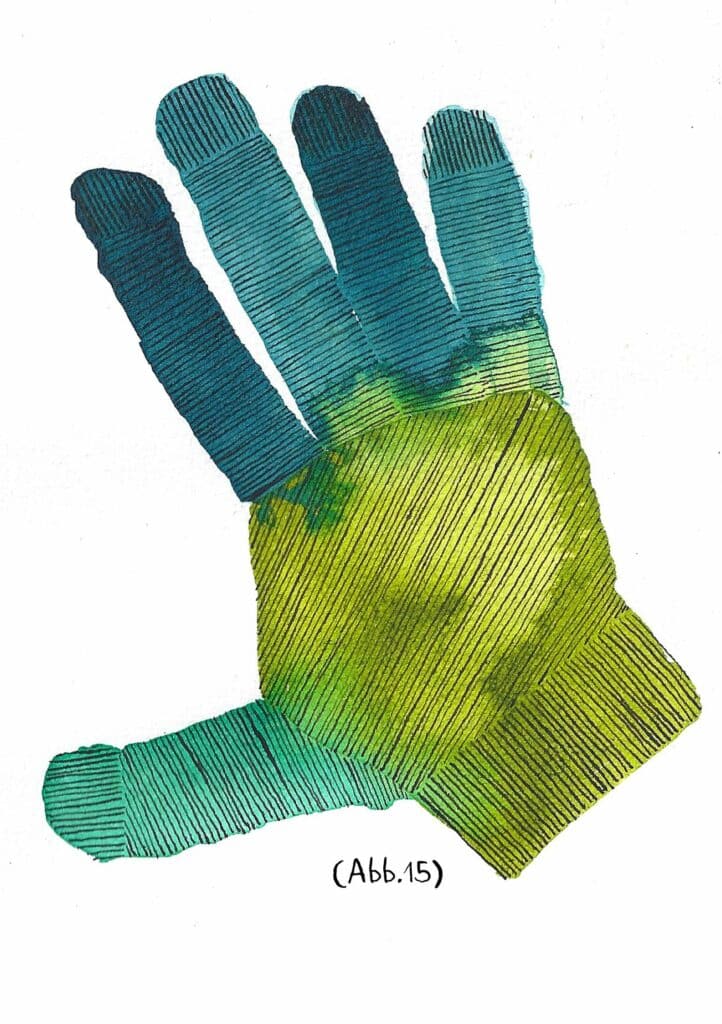

In the next step, I switched to digital work and gave the characters a specific color tone. In Madgermanes, for example, the Mozambicans are colored in an ochre, the GDR citizens remain without coloring. In German Calendar, No December, all the characters have their own color tone, from pink to light to dark brown. Since I prefer to work with only one or two special colors, this solution was too time-consuming and complicated for me. As a result, I left out all skin colors in Lebenslinien, which rightly earned me the accusation that I was acting as if we lived in a “post-racial” society, which is by no means the case. See the Hanau assassination, “racial profiling” and the “Black Lives Matter” movement. So now I am working again in a way similar to the Madgermanes and additionally trying to position myself in the discussion about cultural appropriation, of which I am accused. Again, I can only listen, learn and keep searching. But I will not stop drawing. (Fig.15)

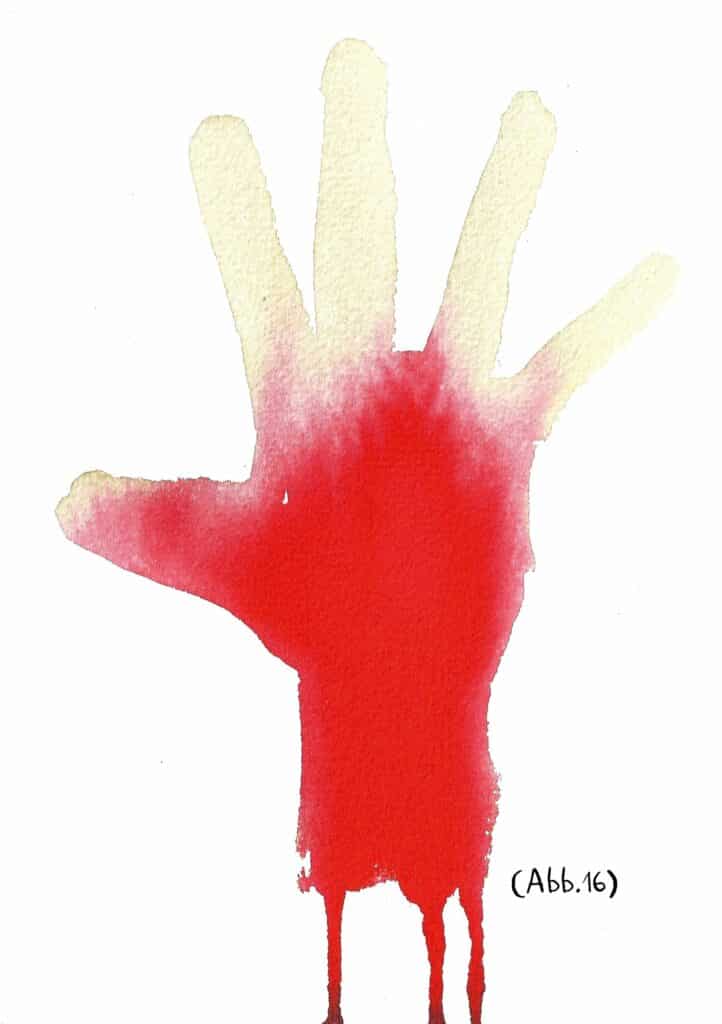

And that brings me to the Congolese comic. I was in Kinshasa for four days and had the honor of working with fantastic writers in a comic workshop, including Judith Kaluaji, who has already shared her work on this blog. I got to meet strong Congolese women in panel discussions and had to face uncomfortable questions about colonial heritage (fig.16) and white privilege (fig.17).

Fig. 16 © Birgit Weyhe

Fig. 17 © Birgit Weyhe

I learned a lot, especially humility (fig.18). That’s all I have to say.

Postscript:

Firstly, the Ghanaian wax-print dress turned out beautifully, even though I never wore it.

Secondly, the drawings are not from my packed four days in Kinshasa, but from a drawing exchange when I was in Brazil. Never trust anyone who claims to be an expert. (Fig.19)

Guest author in this article: BIRGIT WEYHE

Website: https://birgit-weyhe.de/